“Così lavorare con un Nobel ha ispirato la mia carriera”: il racconto di Torben Jensen, allievo di Rosbash

Intervista a Torben Heick Jensen, ex allievo dello scienziato Michael Rosbash, insignito del premio Nobel per la medicina nel 2017. Un’esperienza che ha segnato la sua carriera da ricercatore

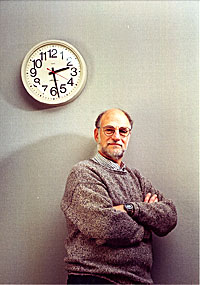

Creatività e coraggio. Insaziabile curiosità, passione per la scienza contagiosa e senso dell’umorismo unico. Sono solo alcune delle qualità che gli attribuiscono i suoi ex studenti e collaboratori. Lui è Michael Rosbash, insignito del premio Nobel per la medicina nel 2017 per il suo contributo alla scoperta dei meccanismi molecolari alla base del ritmo circadiano, che regola, tra le altre cose, anche il rapporto sonno-veglia sulla base dell’alternanza buio-luce. Il numero di ex allievi di Rosbash, attualmente brillanti ricercatori, è elevato. Ne abbiamo intervistato uno, Torben Heick Jensen, che ha lavorato con Rosbash alla Brandeis University e oggi è docente all’Università di Aarhus in Danimarca. Che ci ha raccontato cosa significhi lavorare con un Nobel e dato il suo punto di vista sul mondo della ricerca.

Michael Rosbash (Credits: http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/faculty/rosbash.html)

Dopo aver conseguito il suo dottorato in Danimarca, nel 1998 lei si è trasferito negli Stati Uniti per il suo post-doc nel laboratorio di Rosbash. Come racconterebbe la sua esperienza?

“In quel periodo metà laboratorio lavorava sui meccanismi molecolari alla base del ritmo circadiano, e l’altra metà, tra cui io, sulla maturazione dell’Rna eucariotico. Ho un’alta considerazione di Rosbash non solo come scienziato ma anche come uomo. È ambizioso e intelligente, e di conseguenza esige molto dai suoi collaboratori. Per lavorare con lui bisogna essere sempre al meglio, il che migliora la qualità dell’intero laboratorio. Collaborare con Rosbash agli inizi della mia attività di scienziato ha ispirato, seppur in maniera inconscia, il mio modo di fare ricerca e di dirigere il mio laboratorio”.

In quegli anni lei ha lavorato sulla maturazione dell’Rna. Di cosa si tratta?

“L’Rna è una molecola essenziale per il trasferimento dell’informazione genetica contenuta nel Dna conservato all’interno di uno specifico compartimento cellulare, detto nucleo. Durante la trascrizione nucleare, l’Rna viene formato a partire dal Dna. La molecola così sintetizzata viene poi esportata fuori dal nucleo dove guida la sintesi delle proteine, gli “attori” principali delle funzioni cellulari. Di conseguenza, l’Rna è essenziale per lo svolgimento di tali funzioni le cui istruzioni sono contenute nel Dna. Oggi sappiamo che l’Rna neosintetizzato subisce una serie di modificazioni molecolari prima di svolgere la sua funzione. L’insieme di queste modificazioni si chiama maturazione dell’Rna. Quando ho iniziato la mia carriera si sapeva poco sull’Rna ed era, quindi, un campo di ricerca entusiasmante. In quegli anni ho iniziato ad occuparmi dei meccanismi nucleari di controllo di qualità, ossia tutti quei sistemi molecolari alla base della decisione della cellula di esportare o degradare gli Rna prodotti”.

Torben Heick Jensen (Credits: http://pure.au.dk/portal/en/persons/torben-heick-jensen(a08c2bdc-4318-45f1-bb8a-1cabcb464b01).html)

Si occupa ancora di Rna?

“Sì, la sua complessità e flessibilità mi affascinano. Oggi questa molecola è più conosciuta rispetto ad allora. Per esempio, sappiamo che esistono Rna con funzione enzimatica, o altri necessari per assemblare alcuni complessi molecolari. Esistono anche Rna non codificanti (ncRNA), così definiti poiché non codificano per la produzione di proteine, e la cui funzione è ancora da definire. Nel mio laboratorio ci occupiamo dei meccanismi attraverso cui la cellula definisce quali Rna degradare e quali no. La domanda della nostra ricerca è: come fa la cellula a decidere quali Rna sono funzionali e quali invece degradare rapidamente, per evitare che altrimenti, nella peggiore delle ipotesi, interferiscano gravemente con alcune funzioni cellulari”.

Nel discorso dopo la cerimonia del Nobel, Rosbash ha parlato del supporto governativo alla ricerca di base, “che attualmente non può essere dato per scontato negli Stati Uniti”. Cosa pensa della situazione della ricerca di base in Europa e cosa significa essere un ricercatore oggi?

“Parlare di Europa è complicato, perché è fortemente diversificata e in alcune nazioni il finanziamento alla ricerca gode di una salute migliore rispetto all’Italia, o l’Europa meridionale in genere. In Danimarca, esistono un paio di ricche fondazioni private piuttosto grandi che finanziano la gran parte della ricerca. Come molti ricercatori, dedico molto tempo alla richiesta di questi fondi. Tuttavia, penso che sia anche una cosa positiva, perché per scrivere un buon progetto devi davvero riflettere bene sulla tua ricerca e, inoltre, la competizione è uno stimolo importante. Ottenere semplicemente finanziamenti senza competizione alla lunga produrrebbe una ricerca di bassa qualità. Questo sistema funziona bene quando ci si può fidare delle istituzioni e si è sicuri che le ricerche siano state finanziate esclusivamente per il loro valore scientifico. È questa fiducia a garantire il funzionamento del sistema”.

Immagine in evidenza: credits to Scott Eisen, HHMI (https://www.hhmi.org/news/rosbash-awarded-2017-nobel-prize-physiology-or-medicine)

Interview to Torben Heick Jensen, alumnus of Michael Rosbash, winner of the Nobel prize in medicine in 2017. Jensen talks about his working experience with the scientist and how it influenced his career

Creative and fearless. Insatiable curiosity, contagious passion for science and unique sense of humour. These are only few of the things that his alumni and colleagues say about him. He is Michael Rosbash, winner of the Nobel prize in medicine in 2017 for his contribute to the discovery of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm, which regulates also the sleep-wake rhythm linked to the dark-light cycle. The number of successful scientists he has trained is striking. We interviewed one of them, Torben Heick Jensen, who worked with Rosbash at Brandeis university, and he is now professor at Aarhus university in Denmark. We asked him about his experience with a Nobel scientist, what does he work on and what does he think of current science world.

After getting your PhD in Denmark, in 1998 you moved to USA and you started your post-doc in Rosbash lab. How would you describe your experience?

“At that time half of his lab was working on the molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm, and the other half, including me, was working on eukaryotic Rna processing. I value him as a person not just as a scientist. He is very demanding, since he is very ambitious and really smart, so you have to be at your best performance if you want to interact with him, which is positive because it really sharpens the work. So, we were really talking about science and work all the time and for long time. I think this was important for me to figure out that I wanted to work with this for the rest of my life. It was a substantial experience and I think it defined the rest of my career. I don’t think about it directly, but many of the things we do in the lab or the way it is set up, is inspired from what I saw in his lab”.

Torben Heick Jensen Laboratory at Aarhus University (Credits to: http://mbg.au.dk/forskning/forskningscentre/torben-heick-jensen-laboratory/pictures/)

You were working on Rna processing. What is it?

“Rna is an essential molecule to transfer the genetic information from Dna, located in the nucleus, a specific cellular subunit. During nuclear transcription, the Rna is formed starting from Dna. The new molecule is then exported out of the nucleus to make proteins, the main actors of cellular functions. Therefore, Rna is essential to allow these functions, whose instructions are written in Dna. Nowadays, it is known that the neosynthesized Rna undergoes some molecular modifications before playing his cellular role. These modifications are known as Rna processing. When I started my studies, it was a very interesting time, because many things were being discovered. In those years we began considering the concept of nuclear quality control as cellular mechanisms deciding if an Rna should be exported or whether it should be degraded in the nucleus”.

Do you still work on Rna?

“Yes, Rna has a lot of flexibility and possibility which make it very interesting to study. Nowadays we know more about Rna. For example, Rna can also have enzymatic functions as proteins do, and it can also be a structural molecule needed to assemble other complexes. But there are also many things we still don’t fully understand. There are some so called non-coding Rnas (ncRNAs), which don’t encode for proteins, and we still have to define some of their functions. The big question of my lab is how the cell can figure out which of these Rnas are important and which are not so they have to be rapidly degraded, otherwise, in worst case scenario, if they are not degraded rapidly enough, they might disrupt some cellular functions by interacting with other things that they are not supposed to”.

In his banquet speech Rosbash speaks about support to basic research coming from government and he says that “the current climate in the USA is a warning that continued support cannot be taken for granted”. What do you think of European basic research and what does it mean being a scientist today?

“Speaking of Europe is complicated, since Europe is very diverse because some countries are doing much better than Italy, or generally Southern Europe, in terms of having decent funding for academic research. In Denmark there are couple of very good and rich private foundations which carry a lot of the funding that academic research needs to run. As a scientist, I spend a lot of time writing grants, but it’s also a good thing because it helps you to sharpen your work, and to get the money in competition with others you really have to think a lot about it when you are applying. I think that the system where researchers are just given money without any grant writing or competition would lead to a very low-quality research. This is a solid system if everyone takes his part seriously and most people trust that is working as efficient as it can. Therefore, most people are quite comfortable that all decisions that are being made, are being made with good scientific arguments”.

Commenti recenti